For me, Memorial Day brings to mind Kanchanaburi, Thailand - location of the Death Railway and the Bridge Over the River Kwai. I grew up here, the survivor's harrowing stories, the war cemeteries, all had a profound effect on me that lasts to this very day . . . here's a story I wrote about one Death Railway survivor who never really made it out . . . S.L.

The Bridge over the River Kwai as it appears today in Kanchanaburi, Thailand

Mike was working under the hood of the jeep, in a shady part of the hotel’s small parking lot, beneath a casuarina tree. When he looked up, one of the little woody conifer cones fell and struck him in his right eye.

The pain felt like a white hot dagger going straight through his eye socket. Mike immediately put the palm of his hand over his eye, almost stumbled making his way into the hotel. The serving girls sat him down, and it became obvious that a trip to the hospital was in order.

“The cornea is torn,” the doctor told him. “But it will heal. There will be no permanent effect to your eyesight.”

Mike went home to the hotel with a bandage over his eye. Afterward it occurred to Mike; he’d accompanied some members of his Thai staff to the temple the week before. They’d insisted he come with them to meet with an important monk, whom purportedly had some kind of mystical insight. Mike had long learned to respect the Thai’s spiritual beliefs. They have a sensitivity to the mystic side of the world that Westerners seem to have lost.

After silently contemplating Mike, the monk placed his hand upon the center Mike’s chest, right over his heart. The monk closed his eyes, bowed his head and seemed to go into a sort of a trance. The monk began speaking in a low, quiet voice. The tone of his voice was strangely metallic, an almost machine-like droning.

The monk’s words were unintelligible to Mike, of course. His Thai simply was not good enough. Afterwards, one of the Thai girls translated. He would have an accident. His right eye would be injured, but there would be a complete recovery and his vision would not be permanently affected.

And so it had come to be.

To cheer him up, the girls who worked in the hotel fashioned an eye patch out of a black lace brassiere. The girls were so petite that not too much cutting and sewing was required to convert the almost tiny brassiere into an eyepatch. Mike was pleased to put it on, and the girls clapped their hands and laughed with glee.

Being one-eyed takes some getting used to. Mike had to turn his head to the right as he walked around, to make up for the limited field of vision. Losing the use of one eye also meant losing his depth perception, which made walking up and down the cliff challenging; especially down. It was like being half-blind.

There is a well-known phenomenon that occurs when a person loses a sense or a portion of one’s senses. The other senses become more sensitive, more acute, to make up for the loss. A blind person’s sense of hearing, and touch, for example, become heightened. Perhaps even the sense of smell.

There is a sixth sense, of course.

In the late afternoon Mike found himself resting around his pool, enjoying a nap in the shade as the Southeast Asian sun beat down. When he opened his one good eye he noticed a schooner – a beautiful ship – not far off shore, heading north, sailing upwind. The ship seemed almost translucent as it crossed an expanse where the sun reflected off the water like burnished brass.

Intrigued, Mike got up and went up the steps to the veranda area. Fetching the binoculars from behind the bar, Mike put one eyepiece up to his good eye to inspect the magnificent sailing ship.

He could not see the ship. The coated polarized lenses cut the glare, but he could not see the vessel upon the water. Mike lowered the binoculars, looking over them and – incredibly - he could see the schooner once more.

Mike looked at the binoculars in his hand, looked out at the tall sailing ship on the water, then lifted the binoculars to his one good eye once again.

Again, the schooner was no longer visible. Mike regarded the binoculars. Perhaps it was an effect of the prisms, from holding the binos sideways up to his good eye. He tried reversing them, looking through the other eyepiece but the effect was still the same. He could see the schooner with his naked eye, but the ship simply was not there when he observed through the binos.

Then he looked again at the schooner, magnificent in the yellow sunshine. Her bow raised and fell slightly as she tacked upwind, her gaff-rigged mainsail and mizzen, and gaff top sails full of wind. It occurred to him that the ship had been moving under full sail for at least thirty minutes, and yet didn’t seem to have made any headway in the entire time he’d been looking at it.

Mike looked at the binoculars again and shook his head. Only able to see with the naked eye, not visible through the binos. The strangest thing.

That night at the bar the eye patch drew predictable comments that evening from the usual gang. When Mike caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror behind the bar, it brought to mind the story about his great-grandfather Tom. Tom and his brother were kidnapped by pirates in the South Pacific, and were obliged to become pirates themselves – against their will - for the better part of a year.

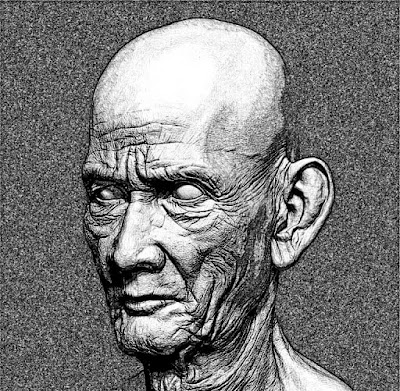

A stranger walked into the Long Bar. The place was relatively quiet, most of the regulars hadn’t rolled in yet. Mike sized up the patron; medium height, faded light blue short sleeved shirt – the sleeves had been cut off, actually - and khaki shorts. Tanned a deep nut brown, wizened and wrinkled but wiry, he could have been anywhere from thirty to seventy. Balding, his sparse salt-and-pepper hair was close cropped, he had an almost bullet-shaped head. There were ropy muscles on his arms and legs; the man was in good shape. He sat at the bar.

“I’ll have a beer, please,” he said. When Mike served him, he noticed the man’s fingernails; thick, hard, almost like an animal’s claws, closer to horn than fingernails. This man had done hard physical labor for a long time in his life.

The stranger picked up the glass with both hands and sank the quart greedily, as if to quench a terrible thirst.

“Thanks,” he gasped, putting the glass down. “I’ll have another, please.” He took a regular pull at his beer this time and put it down.

“Do you know the difference between a war story and fairy tale?” the old man asked, squinting at Mike. Then, without waiting for a reply he continued. “A war story starts out with: “There we were, no shit," while a fairy tale begins with: “Once Upon A Time …”

Mike chuckled at this. “Truth.”

The stranger spoke with a southern American accent, but not a thick drawl. Mike noticed the effect of many years spent overseas. Among the expat crowd, accents clearly identify Australians, English or North Americans, but over time heavy regional accents fade, the edges of a twang ‘round off’. Sometimes an Englishman pronounces a few words in a clear, North American accent, or an American pronounces his r’s as in the English or Australian style. Mike called this phenomenon ‘slipping into neutral.’

There was a silence, a kind of uncomfortable pause. The stranger stared out over the veranda into the inky tropical darkness. “I can never get over how dark it gets,” Mike said, to make a bit of conversation.

“It ain’t jungle dark,” the stranger replied. “There ain’t no darkness like how black it gets in the jungle. Canopy so thick no natural light penetrates . . . no stars, moon, nothing.”

“You know, the jungle out there can literally swallow a man whole. It’s as much a wilderness as the middle of the Sahara, or even in the middle of the Arctic, in its own way. Those poor bastards up on the Death Railway, the River Kwai . . .”

“Yes,” Mike replied.

“The camps in Kanchanaburi had no wire, you know. There was no way to escape; the jungle saw to that. They might as well have been on a prison island. The jungle would eat you up. Between the lack of anything to eat, the bloodsucking leeches and the bugs, and then the tigers, what could you do? Where would you go?”

He paused, staring out at the darkness. A moonless night in the tropics is so utterly dark that it seems to encroach upon a person’s soul. One can almost feel the darkness on one’s face, like black velvet dipped in India ink.

“There was no escape from the Death Railway. The jungle would eat you up. The only way out of that thing was Death itself . . .” He seemed to be speaking as much to himself as to anyone else.

“Yep,” Mike replied. “I always thought that’s what happened to Jim Thompson.”

“Eh? Who’s that?”

“Jim Thompson. You’ve heard of him,” Mike said. He almost added ‘of course?’ but it seemed redundant.

“No,” said the man. “Who is he?”

“Jim Thompson, one of the first expats back in Thailand after the war, revitalized the Thai silk industry, got it started up again almost single-handed.”

“After . . . the war . . .” the old man responded, cryptically.

“He made Thai silk world famous,” Mike continued. “His company still exists. His house in Bangkok is a showpiece, a museum full of pieces of Asian art and artifacts.”

Mike thought it strange that in this day and age anybody with more than a day under their belt in Thailand or Malaysia didn’t know who Jim Thompson was, and his patron at the bar certainly looked like an ‘Old Asia Hand’.

“What about him?”

“He disappeared one day, up in the Cameron Highlands.”

“Ah yes,” the odd old man said. “The Cameron Highlands. Central Malaya.”

Mike caught the use of the old colonial name for Malaysia. Peculiar.

“Yes, he went for an afternoon walk, by himself, and disappeared completely. Never seen or heard from again.”

“The jungle can do that. What was he doing up there?”

“Visiting friends, staying at their villa. At the time of his disappearance, Jim Thompson was probably the richest white man in Asia. His disappearance simply made no sense.”

“Well you know, one step into that jungle and a man can be completely invisible. Maybe a tiger got him?”

“Possible, but there were no reports of a man eater in the area, either before or after his disappearance. Malaysian tigers aren’t really known for hunting humans, not like the Royal Bengals.”

“Ah yes, up in the Bengal,” the old man stated.

Again, Mike thought his use of another anachronistic place name – ‘Bengal’ – odd. Not West Bengal, or Bangladesh. Just Bengal.

“Jim Thompson was OSS during the war. That’s how he ended up in Thailand. He worked with the Thai Serai - the ‘Free Thai’ – during the Japanese occupation, and then helped sort things out in the confusing days right at the end of the war. Later, he was reporting on conditions in the countryside and that’s how he got involved in the silk trade.”

The old man looked at Mike curiously. Mike had a strange sensation that his mysterious guest didn’t quite understand what he was saying, almost as if he were speaking a foreign language.

“You know,” the old man said quietly, “A man can get sucked into that jungle, so deep and thick it really is like . . . the Land that Time Forgot . . . I’ve seen things so deep into that dark green Hell, a man wonders if he’s still on the same Earth, of the same time and place from whence he came . . .”

Mike tried to be discrete as he sized the man up. There was a tattoo on his left forearm, faded but still quite legible. It featured a topless woman in a grass skirt, playing a ukulele.

Mike had seen this kind of tattoo before; it was an old fashioned design, popular with sailors in the thirties and forties. Beneath it were two stars – very faded and blurry, they looked hand done, with a sewing needle perhaps. Beneath the two stars was a scroll with lettering, faded but neater than the stars, professionally done, like the woman. The words read:

U.S.S. HOUSTON – CA-30

His mysterious guest was obviously a Navy man.

Some of the regulars were beginning to make their way in. Mike moved around the bar, the conversation with the stranger was over. As the night went on Mike didn’t notice when the man left, which was strange as his good eye was towards the entrance of the bar. He wasn’t even sure if the man had paid or not. It didn’t matter; patrons often returned the next day to settle up their bill.

The next morning as Mike sat down to begin his writing ritual, he remembered the strange guest from the night before. The man’s tattoo, in particular. Out of curiosity, he did an Internet search for USS HOUSTON:

‘Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, USS Houston got underway from Panay Island with fleet units bound for Darwin, Australia, where she arrived on 28 December 1941 by way of Balikpapan and Surabaya. After patrol duty, she joined the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) naval force at Surabaya.

‘From 4 to 28 February 1942, USS Houston fought three engagements; Battle of Makassar Strait, Battle of Java Sea, and Battle of Sunda Straight. At Sunda Strait Houston suffered four torpedo hits. The Houston rolled over and sank at 0030 hours, her ensign still flying. Of the original crew of 1,061 men only 368 survived. These men were interned in Japanese prison camps and served as slave laborers on the infamous Death Railway in Kanchanaburi, Thailand.’

Mike looked out across the veranda to the heavy foliage on the side of the cliff. Even at the edge of the jungle, the intense vegetation presented a visual cacophony of green upon green. Viewing it one-eyed, with no depth perception, made it all the more overwhelming.

The strange old man’s words seemed to ring in his ears.

“A man can get sucked into that jungle, so deep and thick . . . I’ve seen things so deep into that dark green Hell, a man wonders if he’s still on the same Earth, of the same time and place from whence he came . . . it really is like the Land that Time Forgot . . .”

The jungle beckoned. Mike did something he’d never done on the cliff; he walked into the jungle.

An experienced outdoorsman, Mike was not concerned he’d get lost or disoriented. The cliff was roughly north-south, he was heading north, and if he did lose his way all he had to do was descend to the beach and move south back to the stairs that led up to the hotel. Impossible to get lost.

It was less than ten steps into the green intensity that the confusion set in.

The lay of the land changed, he no longer seemed to be on a semi-vertical cliff. Mike quickly lost any sense of direction, or orientation.

Mike looked up, and in a hole in the canopy against the white sky . . . he could swear he saw a pterodactyl fly by . . .

This story was partly inspired by an experience I had one night long, long ago, at one of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in Kanchanaburi. We must never, never forget their sacrifice . . .

- STORMBRINGER SENDS